Deconstructing the Nation-State, Part II: Power, Knowledge, and Paradigm Shifts from the Margins

JGLR in conversation with Sujith Xavier and Janice Makokis

10/13/202514 min read

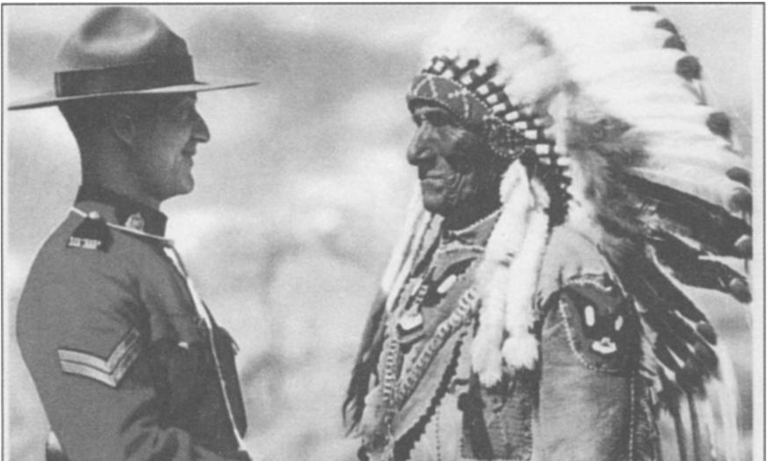

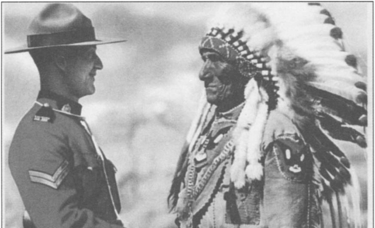

Featured image: Eva Mackey, "Universal Rights in Conflict: “Backlash” and “Benevolent Resistance” to Indigenous Land Rights" (2005). The Benevolent Mountie Myth "presents an idealized image of First Nations' relationship with the government of Canada", obfuscating the colonial history and dynamics of Settler and Native.

Previously, Prof. Sujith Xavier and Prof. Janice Makokis talked with Juris Gentium Law Review regarding the coloniality embedded in the nation-state model, the statist international legal system, and its implications for Indigenous and Third World communities. In this second part of the conversation, we seek to interrogate the role of knowledge and power in such colonial order, and how solidarity can become a keystone in the shift to reimagine possibilities beyond. From the erasure of Indigenous legal orders to the limitations of “legal pluralism,” we reflect on what it means to shift our legal paradigms away from Eurocentricity. We are then challenged, and invited, to inherit these blueprints and dream up futures rooted in alliance and humility. For students and thinkers across the Global South, this is also a call to action: to deconstruct and rebuild.

III. Foundational Distributions of Power-Knowledge

VELIN: As mentioned in the earlier question and highlighted in Prof. Makokis’ work, there have been numerous efforts, discourse, and even critiques (as we’ve previously discussed) aimed at moving beyond colonial ways of thinking, including the state-centric model system in international law. Despite that, the nation-state model continues to dominate as the primary threshold for recognition and participation within the international legal system. Why do you think statehood remains the dominant threshold for legitimacy in international law? Is it related to Prof. Xavier’s explanation regarding their monopoly on violence?

Prof. XAVIER: To answer that question, maybe let me break up my response into two buckets.

First, on power, and the way in which it is distributed; the reason why the nation-state still remains the biggest player in the global structure is because certain powerful entities have retained control. If we think about the UN Charter itself, sovereign equality is enshrined and given to any entity that satisfies statehood criteria. Every polity wants to become a sovereign entity; that’s the only way in which you can participate in the larger global order. Here, we need to think about how power is distributed through law, through the UN Charter and the requirement of statehood, to participate.

Then, there’s the UN organs: the Security Council (UNSC) has five permanent members who have the right of veto, and ten non-permanent elected members. So, the reason for the current structure, and why nation-states remain at-the-table, is because we are trapped. We are told, in order to effect change and bring liberation for marginalized people, you need to become a state. But the moment you enter that structure, you become intertwined, enmeshed, and ensnared in it, where you are stuck between powerful entities like Russia, the USA, the UK, France, and China, who retain the power of veto.

Thus we must think about the global distribution of power: the apex, the G7 countries, and the Global South. We see how money (a form of power) and violence (another form of power) all flow in and out of these apex entities, which are descendants of empires (although we can perhaps think critically about China and Russia). So, when we ask why they are still around, it is because they distribute power.Second, interrelatedly, on knowledge; Edward Said has this beautiful 1983 essay called “Traveling Theory” (p. 226), where he looks at how ideas travel and shape the way in which we think about those ideas, depending on where such ideas land. In the international law context, what’s fascinating is the way in which legal ideas from the Global North migrate to the Global South; and this comes back to our notion of statehood. I’ve been spending a lot of time in the archives reading and thinking about how Sri Lanka became Sri Lanka—and before decolonization (pre-1948), several British scholars and lawyers went back to help set up that infrastructure—the constitutional order that would later become Sri Lanka.

So, here you can see knowledge moving, but it is being structured through a Western lens. The idea of statehood is being sold to these emerging states like Sri Lanka, yet at the same time, what Sri Lanka is doing internally is limiting its own Indigenous peoples, the Tamil people, and the Muslim people. So knowledge is also a form of power that we need to think critically about (for more on this point, James Gathii devoted his 2020 Grotius Lecture to this issue of knowledge in the international law context).

Those are, I think, the reasons why nation-states continue to be such an important player in international law. And of course, we’ve seen a significant push against that power distribution in the human rights context (e.g. the introduction of individual complaints into the structure), but is it working? I don’t think so; but I also want to be hopeful like Prof. Makokis, because without hope, it’s really hard to continue.

FELICE: I can definitely see similar dynamics in the formation of the nation-state of Indonesia. How in the process of “independence” itself, some parts were negotiated with and ushered in with the help of the former Dutch colonial administration, how that also serves a greater agenda—Indonesia is a very big archipelago, it has many different (sometimes conflictual) cultures. So the concept of Indonesia itself as a “unity” in diversity (such is our national slogan) is, in itself, a strategic policy that needs to be constantly repronounced in order to reproduce Indonesia’s legitimacy as a united state.

Prof. MAKOKIS: Let me build on what Prof. Xavier talked about with respect to power, and how this nation-state model exists to reproduce itself to maintain settler power. I'm going to use the example of indigenous peoples and nations that exist within a state (I’m going to refer to Canada as a state, not a nation-state, because it inherited the legal government treaty obligations from the crown of Great Britain). What exists within Canada is: if we theoretically use the model of statehood and give statehood to all indigenous peoples in Canada, it would destabilize the country and the economy. It would bring into question the ability for Canada to exist on its own, and to participate in the international community.

Speaking to what Prof. Xavier mentioned, I think states maintain the Westphalian model because that power needs to be perpetuated for them to exist. Because, if they give over six-hundred First Nations in Canada the status of statehood, it destabilizes the country. And let’s just be honest, that’s not going to happen, because it brings into question the ability to extract resources from our territories. We fuel the Canadian economy. And thus comes the violence, which is evident, when we do push back against these situations. It happened to the Wetʼsuwetʼen people with the Coastal GasLink pipeline, when they were brutalized by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) (see: Amnesty, 2023 and 2024; Sanderson, 2020). The State brought in the police to take them off of their territories and lands, because they were advocating for their rights on their unceded territories. And so the model exists because it has to maintain the power of the state, its access to lands and resources, which fuel the economy for the settler-state to maintain itself and its power. Such is the reproduction and maintenance of settler-state governments and ideology.

This is why it’s so important that we have these critical conversations, so that we’re poking holes in these problematic Western/Eurocentric narratives that benefit only certain peoples, and oppress a large number of other peoples and nations that have their human rights violated daily.

IV. Legal Pluralism in (Non-) Action

VELIN: As highlighted in Prof. Makokis’ work, “Envisioning an Indigenous Jurisdictional Process: A Nehiyaw (Cree) Law Approach” and Prof. Xavier’s work, “Truth, Freedom and Solidarity: A Reflection on Solidarity between Indigenous Peoples and Settler Refugees of Colour”, the current legal system still fails to incorporate indigenous laws and indigenous peoples’ distinct ways of living. Instead, it remains entrapped in Western ways of thinking that ultimately marginalizes indigenous communities, as previously discussed. Do you think international law has the capacity to meaningfully accommodate legal pluralism, or does it inevitably absorb other legal traditions into a dominant, Western (statist) legal logic?

Prof. MAKOKIS: Given my experience and doing this work over the past 15 years, I think I started with hope that there was the possibility that the international community and UN bodies would recognize, respect, or honor indigenous laws in terms of legal pluralism. But, I have to say that I’m very disappointed from what I’ve experienced and seen, because it’s still within the framework of this nation-state model.

I’m going to give an example; when the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was accepted—I know it’s not a convention, but it’s an instrument of international law that can be included in domestic law, to lend persuasiveness when dealing with issues related specifically to indigenous people. The original declaration was drafted by indigenous peoples, but as it went through iterations and variations in the UN system, and finally became the final version accepted by the states—I understand from people that participated in this process, that the only way that it would get accepted is through the addition of one particular Article 46.

Thus, you have all these very powerful statements that speak to self-determination, recognition of free, prime, informed consent, return of lands, including indigenous knowledge as part of education… then, at the very end, Article 46 says “nothing in this declaration shall dismember or impair the territorial integrity of the nation-state.” To me, that speaks to our rights, laws, and legal orders having to still be subsumed within the nation-state. That’s where reality sets in for me, that this idea of “legal pluralism” in recognizing indigenous peoples, laws, and legal orders, again, has to be recognized by the state and fit within state frameworks that do not disrupt, dismember, destabilize the state, the economy, and remain within the national interest.

So, I’m at the place now where I still have to have hope; but that hope comes from building alliances, allies with like-minded people, to push the boundaries of these conversations, to critically analyze and critique these systems and narratives. To teach law students to see the problems with what we’re talking about, so that when they are practicing-lawyers in these areas, they’ll create arguments that address the criticisms we talked about, and it pushes the law further. This is where we see slow progress. Will I see it in my lifetime? I don’t know. But maybe in the next generation of students, lawyers, thinkers, and practitioners—that’s where we’ll see these incremental steps of change happen.

Prof. XAVIER: Coming back to the question around whether international law has the capacity to meaningfully accommodate legal pluralism; in my view, legal pluralism is also a particular framing. If we think about the way in which legal pluralism was articulated by Sally Engle Merry (and others) in the early 1960s, it was a way to think about how multiple legal orders interact with each other, sometimes on top of or in-between each other, etc. One of the things I’ve been struggling with is to conceptualize the way in which legal pluralism operates, and separate it from its origin story, that is, anthropologists going out and watching Indigenous people live their lives. Legal pluralism itself is embedded in this liberal framework of understanding a legal order through your own encounter with that legal order. How do we break out of that space?

Then with that critique of legal pluralism, we also have to think back to the critique of international law, that it was forged as a way to deal with the encounter of the colonial people that existed. When you think back to the 1400s, when Henry the Navigator left Portugal and went out into the world, he found Black bodies, Black people that he wanted to enslave. And international law is used to facilitate that. Thus, how do we remove the historical context in which international law evolved? And how do we juxtapose that with the formation of legal pluralism as a theoretical framework? I think those are theoretical questions that we need to think about as we move through.

For me, in thinking through this question, we see that international law has “the ability” to do that. But if we peel the layers, what we’re actually confronted with is a Western-centric notion of international law that is trying to deal and grapple with the local—and I’m not sure if it’s able to do so. And framing it through the lens of legal pluralism may not be that helpful, because in Prof. Makokis’ tradition (from my limited understanding of it, sitting in Indigenous Legal Orders class at Windsor Law with the first-year law students because I wanted to learn more about it), what I understand is that each Indigenous legal order has its own legal normativity. The six-hundred communities in (so-called) Canada each have their own respective legal normativity, so how do those legal orders interact with each other? How do they interact with my Tamil legal order?

“Do they have the capacity to understand each other?” is an even larger question. From what I understand from Prof. Valarie Waboose (who was my teacher at the University of Windsor), the way in which the Anishinaabe people think about their legal orders is through various principles of humility, bravery, etc. For those of us that are Western-trained in law, how do we even understand bravery as a legal concept? How does that fit into criminal law? So here, I think we have to face the fact that international law may not have the tools that we need right now. But do I want to throw out international law and say, it’s not that relevant, let’s burn it down? No. I, as a lawyer, have an obligation to my clients.

In that sense, I think what Prof. Ruth Wilson Gilmore has given us through abolition, geography, etc, is to say, look, we need to take up these spaces and dismantle it. Understand that what we’re engaged in is dismantling it and forge something new in its wake. I don’t know how to do that, but I think having these conversations with young people like yourselves is a really good starting point. That’s what I try to do in my classes with my students, to push them to a point where they need to think about the future. Prof. Makokis and I are going to continue teaching our classes and grow old, and the future is not ours anymore; it’s yours. So how can we help people get to a point where we can poke holes in this belief that international law is going to emancipate us—it’s not. In fact, it’ll enslave us.

Prof. MAKOKIS: To build off of that (in terms of getting people to think more critically), one of the questions I always get my students to think about in terms of practicing this notion of multiple laws, legal orders, and jurisdictions; a decolonized way of practicing law—getting used to that practice in our thinking, writing, and everyday going-about-the-world—is “what does it mean to live under indigenous law?” If we were to flip this and say, we’re not going to exist within this Canadian or international legal framework that continues to oppress; what does it mean then, to live under a Third World Approach to International Law? Or what does it mean to live under indigenous laws within an international context? How do we think through those conversations?

It really shifts the conversation and thinking, because they have to come out of this idea that Western statehood and law is the only guiding principle that exists. It puts them in this place of okay, how do I think about this from the perspective of indigenous law and legal orders as an umbrella foundation? Or a Third World approach to law? How do you apply that lens and practice? So when we look at it from that place, it shifts how we apply law, from that perspective. And we get different outcomes. I think this is what we're talking about in terms of destabilizing, decolonizing and looking at things differently. That’s where I want to put my energy. I want to put my energy into rebuilding, reclaiming, revitalizing, and building something new that is in line with freedom, emancipation, and people being able to live who they are, and (for me) the way that Creator intended for us to live on our lands and territories with the original instructions that were given to us.

V. For Students of the Global South

FELICE: Perhaps to end this on a somewhat optimistic note, in line with what Prof. Makokis was saying, what message would both of you like to offer to students or young scholars, especially from the global South, who want to challenge the dominance of Western thinking, be it in everyday contexts, theoretical analysis, or praxis, etc?

Prof. MAKOKIS: I think I talk about hope a lot because, when I read some of Paulo Freire’s works—he has this brilliant book on the Pedagogy of Hope—it’s teaching not just independent free thinkers, but also having conversations around this idea of hope. Because if we don’t dream of what is possible and what can be, it is easy to get caught up in this skepticism of not feeling like anything can happen, no criticisms of dominant narratives within these systems; then change does not happen. So in order for transformative generational change to happen, I always talk about and bring students to this place of, you are the future. You are the hope that I have that things are going to change.

This is why I teach from the place that I do and instill critical thinking: so that when you are faced with situations, facts, clients, or files that exhibit these elements we’re talking about, we’ve had these critical conversations. And you can unpack what is presented to you, and offer a different argument that expands, confronts, and challenges existing laws to set new precedents. That’s why I think it’s important to have this idea of hope, so that in our minds—the minds of future lawyers, students, practitioners, and academics—there’s always this chance and idea of pushing the boundary further than our generation did. This is also in line with the indigenous thinking of seven generations, and change happening over time. This is why I always talk from that place, of hope and change.

Prof. XAVIER: I echo and agree with everything Prof. Makokis said. To come back to the question of advice I have for students in the Global South, who are confronting international law and its colonial structures for the first time—my suggestion would be to learn the structures of international law. You can’t understand how international law is prevalent, how it’s deployed, how it impacts people, without understanding the nuances of international law. You need to know the basics first; when I teach International Law, I always get into treaty interpretations—sure, it’s dry. It’s boring. But without treaty interpretation, or Article 38 of the ICJ Statute, we won’t understand how states operate, or the sources of law. Read the cases; because it’s really important to understand how we are governed. For us to take a critical view, we need to understand what it is that the judges are trying to deploy, or what it is they are trying to do.

You also have to realize that you’re not doing this alone. You are not in (say, for example) Indonesia, thinking about these questions alone. Prof. Makokis is in Treaty No. 6 territories; I am in so-called Ontario, yet we are all thinking about these things in parallel. The existing global structures want us to think that we are doing this alone, that we have to go to the UN to make a claim about our experience. But we don’t. What if we start talking to each other instead? What if we start building solidarity between each other, rather than turning to these institutions?

I often remind my students; there are 49,000 lawyers in Ontario, and you will be joining them. The people that are going to give you referrals are your friends sitting next to you in the class. We need to build connections with each other, understand each other, and know where each of us is coming from. Finally, at the same time, we have to do this with humility. We can't think that as lawyers, we know the answer. Prof. Sylvia McAdam, a dear friend, often reminds me to walk slowly and carefully. I don’t know everything there is in this world; I only have my perspective and that is just one perspective. So, we have to approach these issues with kindness and humility.

FELICE: Thank you both. I know it’s hard to have hope, and there has been this rupture and distrust, existential questions, with the status quo and everything that’s been happening. But it has been very insightful talking to both of you. We would totally love to talk to you again in some other opportunity.

This interview was conducted by the editors of Juris Gentium Law Review: Giasinta “Velin” Desvella, Felicia Andryanti (黃), Marecinta Wardhanu, and Bagus Alfandy.