ICC Prosecutor requested arrest warrants on the Palestine Situation: What does it entail and what can we expect?

Scholars and lawyers are currently fixated on interesting developments in international (criminal) law: the Prosecutor’s request to the International Criminal Court (‘ICC’) for five arrest warrants in the situation in the State of Palestine, dated just yesterday. The whole world is watching and great scrutiny is placed on this high-profile case. With two Israelis charged with seven crimes and three Palestinians charged with eight crimes for actions committed or omitted from at least 7 and 8 October 2023, the discourse surrounding this situation brings out many interesting questions, chief of which is whether this application for arrest warrants reflects progress or regress in ensuring accountability and remedies for victims, specifically of Israeli’s occupation and genocide to the citizens of the State of Palestine – atrocities that have been maliciously conducted decades before the violence escalated on 7 October.

Two Israelis and three Palestinians, seven and eight charges: Optical equivalence and a non-tactical targeting to high profile leaders

The two Israelis charged are Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Minister of Defense Yoav Gallant for four counts of war crimes and three counts of crimes against humanity. The other three Hamas high-ranked leaders: Yahya Sinwar, the Head of Hamas; Mohammed Dief, Commander-in-Chief of the Al Qassam Brigades – Hamas’ military wing; and Ismail Haniyeh, Head of Hamas’ Political Bureau, for a combination of eight counts of war crimes and/or crimes against humanity – note that some of the charges coincide between a war crime and a crime against humanity depending on the context in which the crime occurred.

Some notes on the selection of charges

Charges to Netanyahu and Gallant include the war crimes of starvation; wilfully causing great suffering, serious injury, or cruel treatment; wilful killing or murder; and directing attacks against a civilian population. They are also charged with crimes against humanity of extermination or murder, including when caused by starvation; as well as persecution and other inhuman acts. Covered in Articles 7 and 8 of the Rome Statute (’RS’), these alleged crimes were committed or are being committed within the context of both international, against Palestine, and non-international armed conflict, against Hamas together with other Palestinian Armed Groups running in parallel.

Where is the crime of genocide?

Rather surprisingly, no accounts of genocide under Article 6 RS were included despite recent developments on the plausibility of genocide expressed by the International Court of Justice (’ICJ’) (Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel), Provisional Measures, para. 54). This mention of the ICJ is not for random, as South Africa has relied on inter alia the explicit mentions of destruction of Palestinians by Netanyahu amongst other high-profile politicians; along with video footage by journalists, first-hand victims, and the Israeli Defence Force themselves; if the lack of evidence is not an issue, or a big one, questions concerning optics and political considerations arise. On the one hand, aiming at Netanyahu and Gallant is nothing but controversial and politically complicated, so optics might not be the crux of the concern here, on the other hand, charging genocide might just make it more controversial and politically complicated. The question here is, despite that, why hesitate?

Victims' participation and reparations: why it matters

Although the commission of genocide has already been brought before a court, any decision handed down by the ICJ would only put the blame on a State, not the individuals behind their actions. Through the ICJ, reparations to individual victims might not be realistic; South Africa – given its legal standing – might only demand cessation and non-repetition (see page 30 et seq). On top of that, victims are treated as mere witnesses – their voice and interests are treated as ‘passive’ evidence before the ICJ – while the ICC legally centers their interests in the initiation of prosecution and throughout investigations (see Articles 53 and 54 RS), allowing them to speak out against the atrocities that have injured them, their families, and their communities in the trial hearings. On ICC’s order, they can seek monetary and non-monetary compensations (e.g. rehabilitation). Despite its deficiencies, the avenue for victims to participate in the justice process and to earn reparations exclusively exists under the ICC, which provides a unique outlet absent in other international courts. Considering this, it is a shame that genocide is not included in the preliminary drafts of arrest warrants. This hesitance does not seem to have any reasonable justification, and we can only hope that further modifications are made in characterizing certain exterminations done by Israel against the citizens of Palestine as genocide.

Humanitarian aid and other details

Another issue here, more so on the availability of evidence and gravity than optics is that war crimes of directing attacks against civilian objects; humanitarian assistance; undefended buildings, towns, villages, or dwellings; religious buildings; and attacks against entities using Geneva Conventions emblems were not included, despite existing evidence of the destruction of undefended hospitals, civilian camps and constant displacement of the Palestinians with no safe place to go. For instance, the International Committee of the Red Cross, while providing humanitarian assistance, has been attacked while supplying aid in Gaza. One, especially Israel, might argue that their deaths are collateral and not intentional, but investigations into Israel’s precautionary measures – as regulated by international humanitarian law norms – might reveal intent to not only cut off access to food and other basic necessities by obstructing logistics but also by intentionally killing or injuring humanitarian workers.

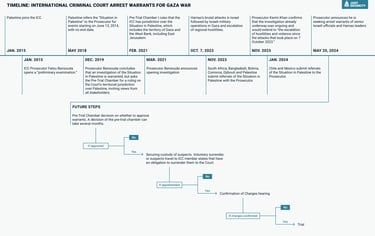

Post-escalation emphasis: what happens to accountability and closure?

It is also incredibly alarming that charges were made on the accounts of actions after 7 October, considering that the Office of the Prosecutor (‘the Office’) has spent a total of 7 years on preliminary examination and investigation into the Palestine Situation since 2015. Based on the allegations of crimes occurring since 13 June 2014, the preliminary examination on the situation of Palestine had been opened since January 2015 by the Prosecutor, had been approved by Pre-Trial Chamber I to proceed to investigations in 2020, and had received referrals from seven State parties since November 2023 following the escalations that began on 7 October 2023. No mention of crimes before 7 October 2023 was made though, which raises doubts on the efficacy of the investigations conducted by the Office since 2020. Does the Office of the Prosecutor rely on, firstly, escalation; and secondly, naked evidence of the crimes?

While it is true that the Prosecutor must act in light of the gravity of each crime (which relies on essentially how grave and how much evidence can 'for sure' prove this), only paying special attention to crimes occurring post-escalation of a conflict does not reflect the Rome Statute’s purpose of putting an end to impunity. Netanyahu and Gallant may have been accountable for crimes before escalations occurred (see OTP, Summary of Preliminary Examination Findings, 2014, paras. 2–5), and for that one might argue that charging them for the gravest crimes post-escalation is somewhat good enough. I have to assert here as a response that the endpoint here is not merely maximizing punishments to these individuals, but closure and reparations to victims and the legal certainty that indeed those who commit the most atrocious crimes will be accountable for each and every one of their actions before 7 October.

Admissibility and jurisdiction: Is ICC overstepping Israel’s sovereignty and domestic jurisdiction?

Some lawyers and scholars have criticized the Office on the admissibility of potential claims, arguing that Israel is able, and has not had the chance to process these crimes domestically; and the jurisdiction, particularly on the issue of personal jurisdiction: that Israel is not a party to the Rome Statute, and therefore Israelis cannot be tried before the ICC. Both the United States and Israel argue that the ICC lacks jurisdiction.

None of these are accurate representations of how the Court works. The determination of admissibility and jurisdiction is first made by the Prosecutor, and later can be challenged by the accused during the confirmation of charges. This requires Netanyahu and Gallant each to appear before the ICC to express their challenges against the case’s admissibility and ICC’s jurisdiction. And even if challenges, are made, they still have to prove that Israel is investigating the exact suspects sought by ICC, which are both Netanyahu and Gallant, for essentially the same charges (See Article 17 RS). So, although they are investigating some Israel Defense Force members, as long as they are not both Netanyahu and Gallant, ICC still has jurisdiction as crimes were arguably committed in Palestine's territory - a State party to the ICC.

Procedural roadblocks: this application for arrest warrants might be ‘momentous’, but for how long?

In this stage of the proceeding, Karim Khan essentially applied, i.e. requested the ICC, to issue an arrest warrant, meaning the warrant has not been made. The Pre-Trial Chamber I Judges on this case (Judge Iulia Motoc, Reine Alapini-Gansoi, and Socorro Flores Liera) will have to judge whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that the person has committed a crime within the jurisdiction of the ICC (see Article 58(1)(a) RS) – a considerably low standard of proof (which makes it all the more absurd that the Office refuses to include genocide to be confirmed).

ICC must approve the issuance of the warrants, and the examination alone may take weeks to several months. There will also be a waiting time required to wait until each of the five suspects surrenders – which could span anywhere from two days to almost two decades.

The following stages – confirmation of charges and the ‘main’ trial – apply higher standards of proof, asking for respectively sufficient evidence to establish substantial grounds to believe (Article 61(7) RS) and that the Trial Chamber be convinced beyond reasonable doubt (Article 66(3) RS). This means that in the next stages – from the issuance of arrest warrants to confirmation of charges – some of the charges approved at the preliminary stage may be modified, in light of insufficient evidence of the occurrence of the crimes or the responsibility of the defendants in causing them.

This does not mean there is no opportunity to modify the charges though. The Prosecutor can ask the judges to amend the arrest warrant (add or modify) (see Article 68(6) RS). Investigations may proceed before the confirmation of charges, and the Prosecutor can modify the charges before the Pre-Trial hearings (see Article 61(4) RS). This entails, with more investigation to do, more charges, especially on genocide, will be included in the following stages. While this is true, this means that it might take weeks to months for the judges to examine all evidence brought upon them, including when modifications are made by the Prosecutor along the way, (again) dragging the entirety of the proceeding.

The hassle does not yet include the massive challenge ICC will face in enforcing its arrest warrants. With no choice but to rely on State parties to surrender the suspects to the ICC or voluntary surrender by the suspects themselves, it is difficult to be optimistic that at least Netanyahu and Gallant would comply. If ICC ultimately issues arrest warrants, the concern here is whether this case will proceed at all.

Despite the legal obligation of all 124 State parties to comply with these warrants (see Article 86 RS), reactions to previous warrants – especially against heads of State – show that securing their cooperation is largely problematic. Omar Al Bashir (Sudanese President) dodges ICC by traveling to Jordan, Uganda, Djibouti, and Chad – and relies on these countries’ lack of cooperation to ICC to flee; Joseph Kony (founder of the Lord’s Resistance Army, Uganda) evaded ICC for 19 years, now suspected in Darfur; not forgetting, Putin’s (and, apparently, the international community’s) blatant ignorance to his arrest warrant. This itself is a huge obstacle in making any legal development whatsoever, as the ICC cannot conduct trials in absentia at least without a ‘good cause’, and might be the only procedural obstacle that we will face before even discussing the material elements of each crime.

Considering all of these factors, the application for an arrest warrant might be quite momentous, but only fleetingly so. Keeping this vital momentum—legally accusing two high-profile leaders of a Western-backed government—requires unwavering international cooperation and steadfast commitment to justice. Without consistent and coherent global efforts, we risk repeating the disheartening precedents set by the Al Bashir’s and Kony’s no-shows. To truly break the cycle of impunity and deliver justice for all victims, the international community must act with unity and resolve, ensuring that this historic move towards accountability is not lost to political inertia and procedural roadblocks. The eyes of the world are upon us, and history will judge how we respond.

Rachelle Tan (known as Ama) is an undergraduate law student from Universitas Gadjah Mada concentrating on international law, particularly exploring international criminal law, international humanitarian law, and human rights. Currently, she is the executive editor at Juris Gentium Law Review, Indonesia’s leading student-run journal.

Image source: International Criminal Court

Image source: Just Security