The US–Indonesia Deal: When “Free Trade” Means Ceding Data Sovereignty

Aliyka Gewang

7/26/20256 min read

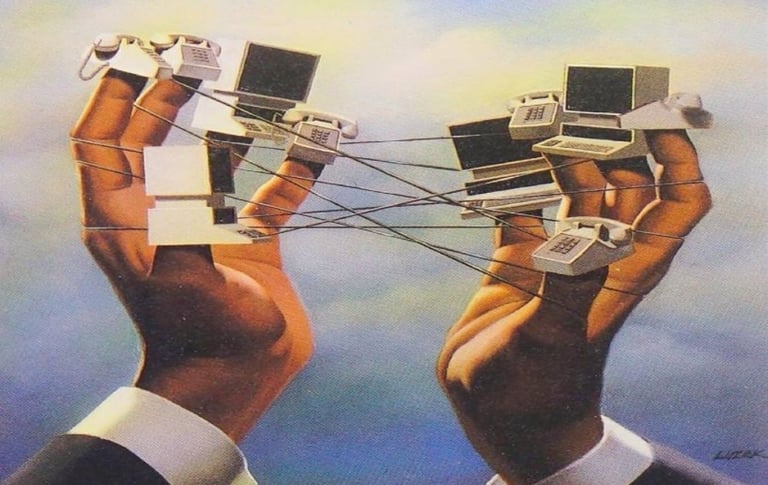

In the new age of control, economic leverage transforms digital information into a tool for exerting influence over nations and individuals. (Image: https://www.cosmos.so/e/846418698)

A joint statement from the White House on July 22, 2025, on the Framework for United States (US)–Indonesia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade has ignited fervent debate among Indonesians, particularly the elimination of approximately 99% of US industrial and agricultural export tariffs against a meager decrease to 19% in reciprocity. Beyond tariffs, the agreement aims to tackle Indonesia’s non-tariff barriers, notably exempting US companies and goods from local content requirements and facilitating $3.2 billion in aircraft procurement as part of forthcoming commercial deals.

But what stood out from this laundry list of dubious assurances is Indonesia’s commitment to provide certainty regarding the ability to move personal data out of its territory through the recognition of US as a country or jurisdiction that provides adequate data protection under Indonesian law.

Data Flow Commitments

In light of this, Indonesia’s Minister of Communication and Digital Affairs, Meutya Hafid, revealed that the purpose of such an agreement is entirely commercial, not for our data to be managed by others, and solely for the exchange of certain goods and services, which require data disclosure. This author finds this to be deeply problematic. This stance dangerously oversimplifies the complex reality of digital trade, where the line between “commercial” and “personal” data is virtually nonexistent. Every commercial interaction generates personal data that is central to a company’s commercial value. From purchasing habits to something as minute as daily screen time, they can fall within the umbrella of “commercial data”.

Notwithstanding, the official White House statements remain the sole source of information. The Indonesian executive remains conspicuously silent, with only an anticipated coordination meeting between the Ministry of Communication and Digital Affairs and the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs, as well as press conferences. We are left to merely hope that clear bounds for this agreement, especially the definition of “commercial data,” will finally be established.

When Data Transfer Becomes a Trade Bargaining Chip

The explicit linkage between substantial economic benefits (e.g., tariff reduction, market access, commercial deals) and Indonesia's commitment to recognize the US as providing “adequate data protection” strongly suggests that trade negotiations are being leveraged to influence domestic data protection standards and cross-border data flow policies. The US, a superpower in digital services, benefits significantly from the free flow of data. We now bear witness to how a country's data protection regime has become deliberately expropriated by trade law.

The agreement effectively pushes Indonesia to align its cross-border data transfer rules in a manner that facilitates US business operations. This potentially bypasses Indonesia's own Personal Data Protection (PDP) Law, indicating a direct economic incentive driving a specific data policy outcome rather than a truly independent regulatory decision.

Article 56(1) of the PDP Law establishes a framework for cross-border data transfers, requiring the receiving country to demonstrate an equal or higher level of personal data protection. Once fully operational, Indonesia’s PDP Agency is tasked with independently assessing such requirements. However, with the existing pre-negotiated “adequacy” assurance, the PDP Agency’s task would be futile. What purpose will the independent assessment serve if President Prabowo Subianto owes President Donald Trump unequivocal certainty?

In hindsight, the US likely possesses a higher capacity for personal data protection than Indonesia, given its abundant capital and resources, especially when compared to Indonesia's shortfall in digital and data protection experts. However, this disparity doesn’t negate the fact that a degree of domestic autonomy is compromised.

This paradoxically limits Indonesia’s ability to domestically regulate data privacy. If trade agreements compel Indonesia to adopt “free flow with trust” principles without sufficient accompanying capacity building, or without allowing for necessary internal safeguards (such as localization of sensitive data), they might find themselves unable to effectively protect their citizens' data. This stands against a fundamental constitutional guarantee: Article 28G(1) of the Indonesian Constitution, which broadly protects individual privacy and self-determination. Ultimately, these concessions are framed as acceptable for the utilitarian benefit of securing trade agreements and fostering economic growth.

Is It, Though?

At its core, utilitarianism is a moral principle which suggests that the ethically correct course of action is the one that produces the greatest balance of benefits over harms for everyone. A core critique of utilitarianism, especially pertinent to data privacy, is its disregard for justice and individual rights. Strictly applied, it condones benefits derived from lies and manipulation. Thus, if sacrificing individual privacy through mass data collection, surveillance, or the exploitation of personal data yields greater collective good—such as economic growth—a purely utilitarian approach could justify these infringements. But even so, a purely utilitarian calculus, focused solely on aggregate economic benefits, fails to account for fundamental ethical principles and individual liberties. While the financial prospects of the trade offer significant potential for collective welfare, deeper ethical analysis reveals serious concerns that a purely consequentialist approach overlooks.

When we look at Indonesia’s decision to hand over its citizens’ private data, it appears to treat people not as individuals with inherent worth, but rather as mere tools to achieve economic gain. This approach clashes with the Kantian deontological perspective, which firmly dictates that humanity must always be treated as an end in itself. This isn’t just a philosophical quibble; it's inextricably linked to a deep betrayal of individual liberties that are essential to a dignified human existence. By guaranteeing this data transfer without proper consent, Indonesia isn't just striking a trade deal; it’s eroding the citizens' fundamental right to privacy and informational self-determination, thereby undermining the vital trust that binds a government to its people.

Furthermore, a strict utilitarian lens falters because it can only truly work if probabilities and outcomes can be objectively quantified and compared, a task inherently challenging when dealing with complex human values like privacy and dignity. In terms of the US-Indonesia deal, the difficulty in objectively quantifying the “harm” of privacy loss versus the “benefit” of economic gain makes a purely utilitarian calculation flawed.

Is the US-Indonesia Approach the New Global Standard?

The inclusion of provisions addressing international data flows and digital trade is an increasingly common feature in contemporary trade agreements, and the predicament remains the same: balancing the economic benefits derived from unfettered data flows across borders with the imperative of a trusting environment for individuals to conduct their digital business securely. While digital trade provisions are common, the specific commitment of one country recognizing another's data protection “adequacy” within a trade agreement, as observed in the US-Indonesia deal, is not a universally standardized practice. This contrasts notably with the European Union (EU)’s firm stance on data protection as a non-negotiable human right.

On the other hand, US-driven agreements, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), reflect a different philosophy. These agreements typically prohibit restrictions on cross-border data transfers for business purposes, often banning domestic data localization requirements. This identical pattern, now evident in the US-Indonesia deal, crystallizes the true American agenda.

This agenda extends beyond trade agreements into legislation of extraterritorial data control. A primary example is the US Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (CLOUD Act), enacted in 2018 during President Donald Trump’s first administration. This act mandates US-based technology companies to comply with legal requests for data, regardless of where that data is physically stored across the globe. Critiques from civil liberties groups, for instance, the Freedom of the Press Foundation, have warned that the CLOUD Act poses “danger to journalists worldwide,” and that it would allow foreign governments to access private data on American soil while circumventing important privacy protections. This illustrates a clear picture of a concerted effort by dominant global powers to shape a digital landscape favoring unimpeded data flow.

The implications are evident: this is bigger than the US-Indonesia deal. The economy, alongside geopolitical imperatives, is posing significant real-life threats to privacy and autonomy globally.

Some Afterthoughts

The Joint Statement on a Framework for US–Indonesia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade exemplifies the utilitarian dilemma faced by developing countries. While the agreement promises substantial economic benefits through market access and investment, Indonesia’s pre-emptive recognition of US data protection adequacy raises questions about the independent application of its domestic data protection standards and the preservation of its data sovereignty. This situation sheds light on how the pursuit of trade liberalization can inadvertently influence or constrain domestic regulatory autonomy. To successfully undergo the complexities of digitalization and international trade, Indonesia should strengthen domestic enforcement capacity by accelerating the operationalization of the independent PDP Agency, rigorously applying the PDP Law’s cross-border transfer rules, and ultimately prioritizing public trust and digital literacy. In all honesty, it is crucial to avoid scenarios where the integrity of data protection is significantly compromised in exchange for trade benefits.

Aliyka Gewang is an Associate Editor at Juris Gentium Law Review and is currently pursuing a law degree at Universitas Gadjah Mada. As an active researcher, Aliyka is involved in multiple projects with esteemed lecturers, with current research focusing on sustainable finance and capital markets.